汪华Vigi Wang

我的80天My 80 days

《我的80天》作品方要仅以线上资料的形式展示,待疫情结束在实施。

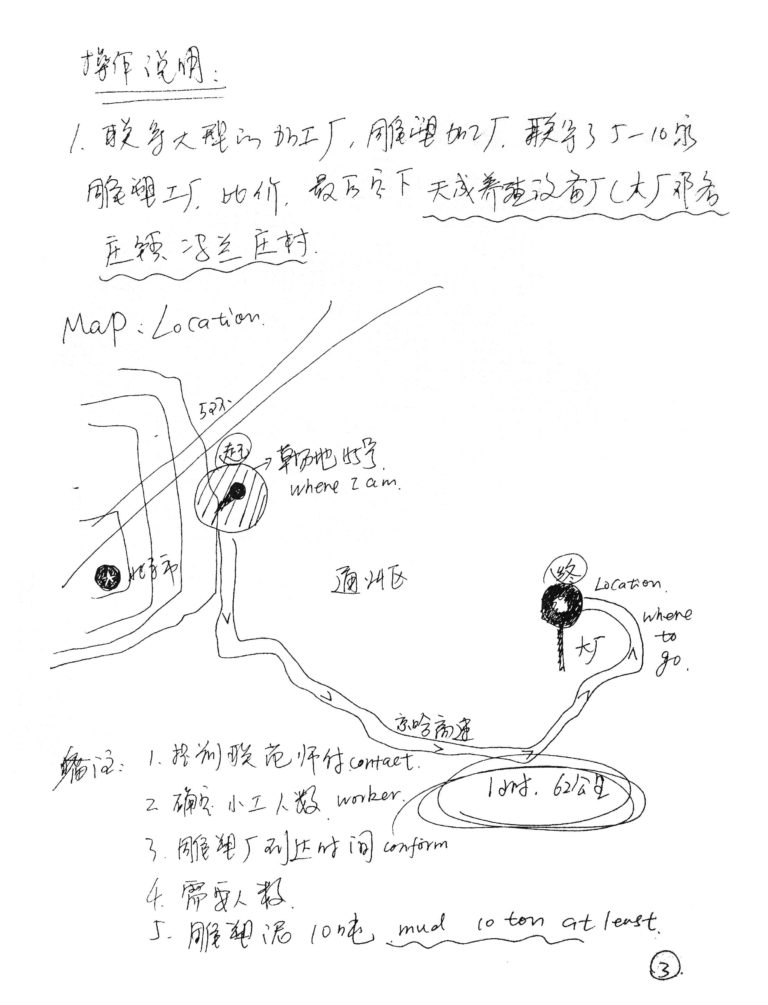

项目说明:

由于在北京工作原因,回到北京。经过 21天的居家隔离,慢慢开始北京的正常生活与工作。然而北京的疫情突然在 6月 11日到 6月 26日仅仅15天内新增297名确诊新冠病例,导致北京从三级响应变为二级防控,不允许聚众,周边工厂也都被迫关闭,原本计划于6月18日实施的项目被迫停滞。待疫情归零后,将再次启动该项目。

2020.7.3

Vigi

北京

The works of My 80 Days should only be displayed in the form of online materials until the epidemic is over.

Project description:

Because of my work, I returned to Beijing. After 21 days of home quarantine, I began my normal life in the capital. However, 297 new Covid-19 cases were confirmed in Beijing in just 15 days from June 11 to June 26, causing Beijing to move from a level-3 response to a level-2 prevention and control. Crowds were not allowed, surrounding factories were forced to close, and the project originally scheduled for June 18 were halted. The project will be launched again after the outbreak returns to zero.

2020.7.3

Vigi

Beijing

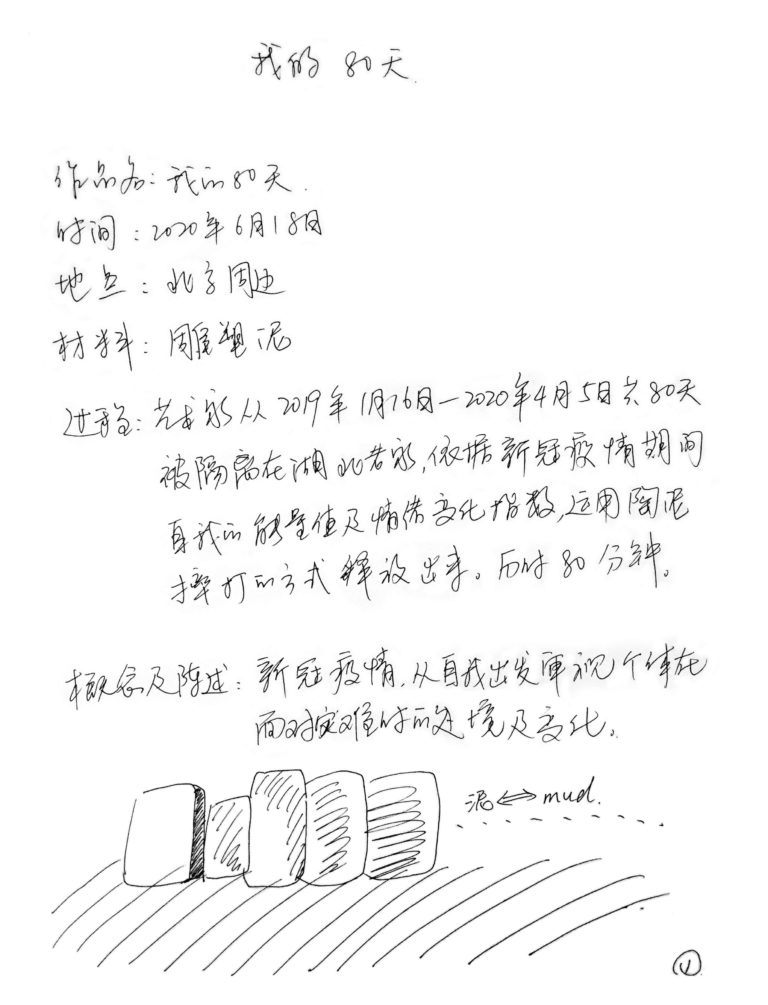

我的80天My 80 days

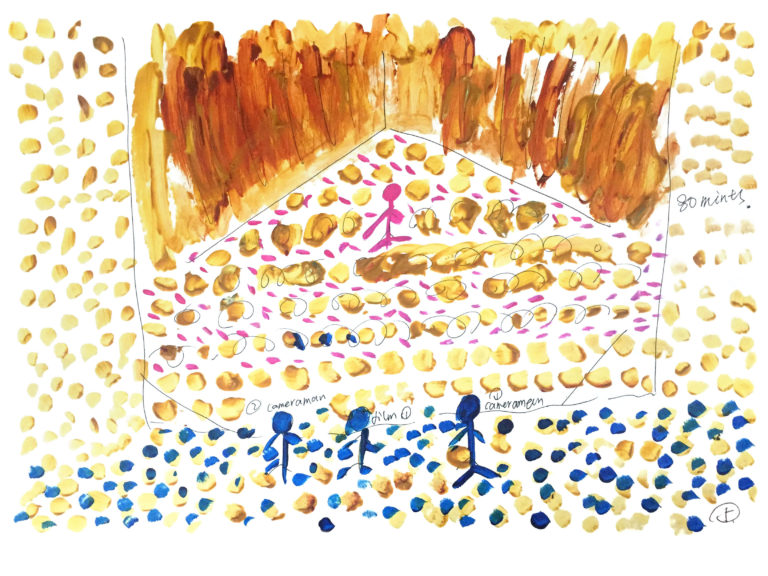

时间:2020年6月18

地点:北京

材料:雕塑泥

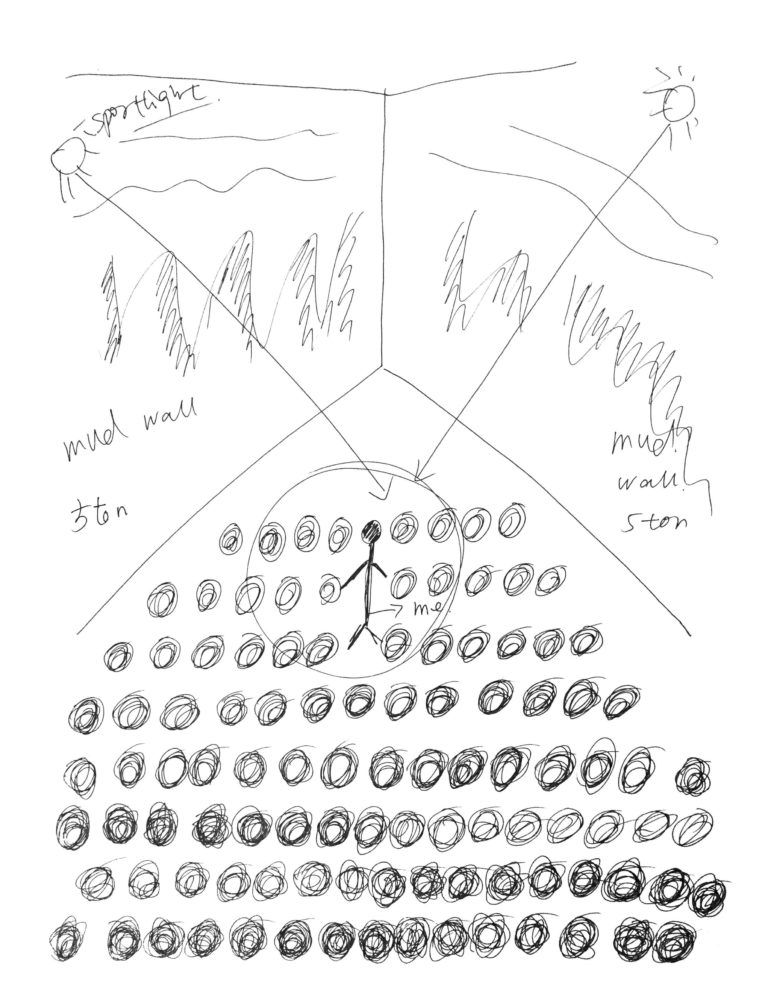

过程:艺术家从2019年1月16日-2020年4月5日共80天被隔离在湖北老家,依据新冠疫情期间自我的能量值以及情绪变化指数,运用陶泥摔打方式释放出来。历时80分钟。

—

概念及陈述:新冠疫情,从自我出发审视个体在面对灾难时的处境及变化

湖北武汉这次突然爆发疫情,我被隔离在老家,没有太多的移动空间,每天都是固定的活动范围,内心产生极度不安、焦虑、愤怒、惶恐、害怕、怀疑、绝望、无助、孤独、哭泣、悲悯、同情、面对、安慰、接受、帮助、祈福……一天天。

运用80个自然摔打成型的陶泥作为80天的变化。

Time: 18th, June, 2020, 80 minutes

Venue: Beijing, China

Materials: mud sculpture

The Process: The artist was self-isolating in her hometown in the Hubei Province for 80 days; from January 16, 2019, until April 5, 2020. During this period she suffered from mood swings and depression and she sought relief by molding mud. The performance lasted for 80 minutes.

—

The new coronavirus epidemic from the perspective of self-examination and personal changes in the face of a disaster

During this sudden virus outbreak in Wuhan, Hubei Province, I was self-isolated in my hometown. Every day there was not much activity and I had to live in a very limited amount of space. I felt extremely uneasy, anxious, angry, frightened, doubtful, hopeless, helpless, lonely, and compassionate. Sometimes I was comforted, accepted, or helped; I felt sad and even cried sometimes, and all this happened every single day.

I shaped 80 pieces of mud, like in a full-contact match, one for each of the 80 days of isolation.

在艺术品中找到意义

Finding meaning in the artwork

我的80天

曹家硕

汪华的作品是《我的80天》。新型冠状病毒爆发后,这位艺术家和全世界数亿人一样,被迫与世隔绝。在这种强加的孤独感下,汪华有时间审视自己的特殊处境,以及去感受病毒的传播是怎样改变她生活的。为了表现她的情绪变化,这位艺术家用她的身体塑造了80块自然摔打而成的陶泥。我们所看到的形态各异的陶泥造型是对她不同情感变化的直接体现:焦虑,愤怒,恐惧,怀疑,绝望,无助,孤独,沮丧,同情等等。阿尔贝·加缪曾经说过,没有一个艺术家能够脱离现实而存在。艺术虽能质疑现实,却不能完全脱离现实。

“我们不断经历的生活变化导致了持续进化的情感流动”

汪华此次展览的作品延续了她之前作品的情感轨迹。《Kalinka 的诞生》是该系列的一个突出例子。这位艺术家被邀请在由她的一个朋友建造的阁楼上创作一件特殊的作品。她选择了一个朋友用了几十年的被子作为艺术材料。被子通常是用来保暖的。它们是日常生活中的实用物品,也是社会关系的纽带。它们的社会性是因为它们保留了使用过它们的人的痕迹:气味和颗粒被留在被子上,成为一层层历史。在这幅作品中,艺术家在被子下反复的穿衣和脱衣以使自己成为这个历史的一部分,从而创造了这些物品所具有的社会特征。通过呼吸和运动,她的身体形状赋予了作品艺术意义。

在《我的80天》中,汪华运用了身体作为表达容器的理念。这位艺术家表达了她的担忧,即一个人的自我感知如何随着环境的变化而发生丰富的变化。这也是我们在疫情期间都经历过的事情:我们不断经历的生活变化导致了持续进化的情感流动。

“在拒绝任何笛卡尔的二元论时,汪华并没有看到身体和灵魂,肉体和精神之间的本质区别”

汪华选择自然摔打的陶泥作为艺术媒介,使她的作品具有明显的抽象性,与表现的显像性相去甚远。在某种意义上,抽象能够表现出人性的本质,以及激发我们内在生活中不可表达的情感。艺术家在谈到《Kalinka的诞生》时说,身体也是一种直接而有效的能够表达人性的物质。身体作为一种载体,是内在情感产生之地。

然而,在《我的80天》中,人体从一个情感的载体,变成了被文明禁锢之“物”——失去了自身的精神。在拒绝任何笛卡尔的二元论时,汪华并没有看到身体和灵魂,肉体和精神之间的本质区别。身体的觉醒使文明成为可能,但同时它也通过社会规范和约束禁锢着我们。

My 80 days

By Cao Jiashuo

Wang Hua’s work is entitled 80 Days of My Life. After the coronavirus pandemic broke out, the artist – just like hundreds of millions of people all over the world – was forced to live in isolation. In such a condition of imposed loneliness, Wang had time to examine her peculiar situation and how the spreading of the virus was changing her life. In response to her emotional changes and mood shifts, the artist modeled 80 pieces of natural clay that were shaped through the use of her body. The different shapes that we see realized are direct embodied expressions of an upheaval of different emotions: anxiety, anger, fear, doubt, despair, helplessness, loneliness, depression, compassion, and so. Albert Camus once said that no artist could live without reality. Though able to question reality, art cannot fully escape the everyday.

“Constant changes in our lived experiences have resulted into a flow of emotions in continuous evolution”

Wang’s work in this exhibition follows a trajectory of emotional pieces that the artist began in her previous oeuvre. In The Birth of Kalinka, a prominent examples of the series, the artist was invited to create a site-specific work that was in an attic, originally built by one of her friends. She chose as artistic material some quilts that her friend had been using for decades. Quilts are usually used for keeping one’s body warm. They are practical objects of daily life, but also a nexus of social relationships. They are social insofar as they keep traces of those who have used them: Smells and particles are left on the quilts, as layers of histories adding to one another. In this piece, the artist repeatedly dressed and undressed under those quilts, becoming part of that history, thus creating that social aspect that these objects possess. By breathing and moving, her body shaped from within the meaning of the artwork.

In 80 Days of My Life, Wang uses this idea of the body as an expressive vessel. Here, the artist reveals her concern about how, in response to contextual shifts, one’s embodied self-perception can change in enriching ways. This is something that we all have experienced during the pandemic: Constant changes in our lived experiences have resulted into a flow of emotions in continuous evolution.

“In refusing any Cartesian dualism, Wang does not see any essential distinction between body and soul, flesh and mind”

In opting for natural clay as artistic medium, Wang imbues her work with a distinct abstract quality, far from the obviousness of representation. Abstraction in some sense is capable of presenting the essence of human nature and its inexpressible feelings animating our inner lives. The artist once said about The Birth of Kalinka that the body is also a direct and effective way to materially express human nature. As a carrier, the body is the locus where inner feelings emerge.

However, in 80 Days of My Life, from a carrier of feelings, the human body turns into a “thing” imprisoned by civilization – it becomes devoid of its own spirit. In refusing any Cartesian dualism, Wang does not see any essential distinction between body and soul, flesh and mind. The awakening of the body is what makes civilization possible, but in doing this it is also what imprisons us through social norms and constrictions.

汪华Vigi Wang

汪华,1982年生于湖北荆州,2005年获得西安美院中国画学士学位,目前工作和生活在北京。她的艺术实践涵盖了多重媒介,包括现场行为、录像、绘画、装置以及现成品等。她擅长将理论概念、私人叙事和成长背景三者相结合,并以其独特的艺术语言和表现方式进行美学化表达。汪华的作品主要强调创作的心理过程与视觉传达形式之间的关系,她多以融合了时间性与空间性以及两者之间的张力关系所激起的催眠式现场行为,来探讨潜意识挪移至现实时知觉产生的似曾相识感与陌生未知属性。因此,汪华的创作通常以私人叙事出发,却能以引起大众广泛共鸣结束。

作为一位艺术家,汪华关注的议题是:个体如何在社会环境中通过自我认知的不断更迭,从而建立更为完整独立丰满的人格。艺术家的任务并不是每天重复机械工作,而是需要不断思考和发现周围,最终带着问题走进大众,并试图为大众的生命体验打开全新的可能性,促进后者追求生命多元化的勇气和信心。

在汪华看来,身体是最直接、最符合人性表达的表现材料。身体作为载体,可以呈现当下的内心感受通过即兴转换后升华了的思想性。她的作品不仅聚焦自我解脱和自我救赎,更试图探讨公众在当下反应、幻想和现实之间来回穿梭辩证的复杂关系。正如法国知觉现象学创始人梅洛·庞蒂所言:“身体和主体其实是同一个实在,身体既是存在着,被经验着的客体现象,又是经验着,意识着的主体。”汪华用身心合一的行为表演,亲身驳斥了如笛卡儿等所宣称的将精神和肉体视作平行关系的二元论,还原了艺术家甚至人类作为具有思想性的心眼相通的灵长生物的尊严。

Wang Hua was born in Jingzhou, Hubei Province in 1982. In 2005, she obtained a BA degree in Chinese Painting from the Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts. She currently works and lives in Beijing. Her artistic practice covers multiple medias, ranging from performances, videos, paintings and installations to ready-made products. Her work focuses on combining theoretical concepts, private narratives and personal backgrounds, which are aesthetically expressed in her unique artistic approach. Wang Hua’s work mainly emphasizes the relationship between the psychological process of creation and the form of visual communication. She mostly explores the sense of déjà vu and the unknown when the subconscious is subverted into the reality through combination of the temporality and space. Therefore, Wang Hua’s creation usually starts with a private narrative but ends with widespread public resonance.

As an artist, Wang Hua pays attention to how an individual can create a more thorough and independent personality through updating one’s capacity of self-perception in the social environment. An artist shall not repeat mechanical work every day, but constantly observe and discover the surroundings, and finally connect to the public with problems she/he provokes, and try to open up new possibilities for the public’s experience through boosting their confidence and courage to pursue diversity in life.

Wang Hua sees the body as the most direct and most effective form of artist expression. As a carrier, the body can present thinking through sublimated feelings. Her work not only focuses on self-liberation and self-redemption, but also attempts to explore the complex dialectic relationship among the public, their instant reactions, and the fantasy and the reality. As Merleau-Ponty said: “The body and the subject are actually the same reality.” With her performances, Wang Hua rebels against the dualism of mind and body, as claimed by Descartes, and restores the dignity of artists and even human beings as embodied creatures that can think.