DABDA

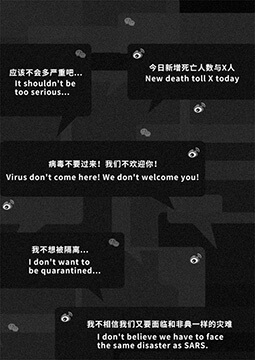

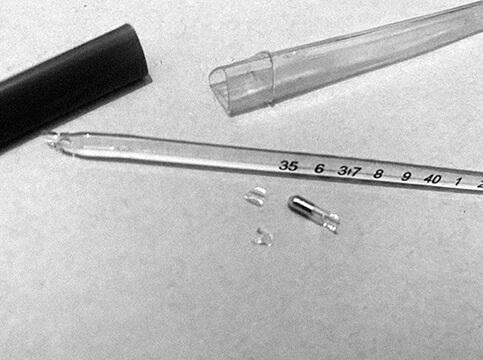

否认Denial

“悲伤的第一阶段能帮助我们不被伤痛击倒。这个时期我们会觉得世界已没有意义,而且让人无法承受,生命失去了目的。我们处于震惊与否定的状态,对很多事情都感到麻木。我们怀疑自己是否还能活下去,即使可以,又为什么要活下去。我们只是过一天算一天。否定与震惊能帮助我们度过最困难的时期,调整悲伤的感觉。甚至可以说否定心态是一种恩典,上天通过这个方式让我们每次只感受到能承受的悲伤。”

伊丽莎白·库伯勒·罗斯,大卫·凯思乐,当绿叶缓缓落下——与生死学大师的最后对话,第5页

“This first stage of grieving helps us to survive the loss. In this stage, the world becomes meaningless and overwhelming. Life makes no sense. We are in a state of shock and denial. We go numb. We wonder how we can go on, if we can go on, why we should go on. We try to find a way to simply get through each day. Denial and shock help us to cope and make survival possible. Denial helps us to pace our feelings of grief. There is a grace in denial. It is nature’s way of letting in only as much as we can handle.”

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler, On Grief and Grieving, p. 37

愤怒Anger

“这个阶段以多种方式展现自己:对您所爱的人感到愤怒,因为他没有更好地照顾自己;或者对您自己感到愤怒,因为您没有更好地照顾他人。 愤怒不一定是逻辑上的或有效的。 您可能会生气,因为您没有看到这种情况的到来,当您这样做时,没有什么可以阻止它。 您可能会因为无法拯救您如此亲爱的人而对医生感到生气。 您可能会生气,因为对您来说意义重大的某人可能会发生坏事……。 它不应该发生,或者至少现在不应该发生。”

伊丽莎白·库伯勒-罗斯和大卫·凯斯勒,《悲伤与悲伤》,第39-40页

“This stage presents itself in many ways: anger at your loved one that he didn’t take better care of himself or anger that you didn’t take better care of him. Anger does not have to be logical or valid. You may be angry that you didn’t see this coming and when you did, nothing could stop it. You may be angry with the doctors for not being able to save someone so dear to you. You may be angry that bad things could happen to someone who meant so much to you…. It was not supposed to happen, or at least not now.”

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler, On Grief and Grieving, pp. 39–40

讨价还价Bargaining

失去亲人之后,讨价还价的形式变成一种暂时的求和:“如果我将余生用来助人,是不是醒来就会发现一切只是一场噩梦?”。我们迷失在“悔不当初”或“假设当初……”的迷雾里。你要人生回到从前,你要亲人回到身边,你要时间倒转,让你早一些发现肿瘤、更早发现疾病,组织意外发生……如果有如果,那该有多好。

伊丽莎白·库伯勒-罗斯和大卫·凯斯勒,《悲伤与悲伤》,页48

After a loss, bargaining may take the form of a temporary truce. “What if I devote the rest of my life to helping others? Then can I wake up and realize this has all been a bad dream? We become lost in a maze of “if only . . .” or “What . . .” statements. We want life returned to what it was; we want our loved one restored. We want to go back in time: find the tumor sooner, recognize the illness more quickly, stop the accident from… if only, if only, if only. We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss. We remain in the past, trying to negotiate our way out of the hurt.”

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kassler, On Grief and Grieving, p. 48

介绍Depression

“沮丧的阶段让人觉得仿佛没有尽头……你会变得退缩,陷入浓得化不开的哀伤,甚至怀疑是否应该独自活下去,活下去是否还有意义。天亮了,但你不在乎。脑海里有个声音告诉你该起床了,但你一点都不想动,也想不出有任何理由要起床,生命已失去意义。起床像攀登高山一样困难,你只觉得十分沉重,根本没有起床的力气。”

伊丽莎白·库伯勒·罗斯,大卫·凯思乐,《当绿叶缓缓落下》,张美惠译 2008版,页53

“This depressive stage feels as though it will last forever…. We withdraw from life, left in a fog of intense sadness, wondering, perhaps, if there is any point in going on alone. Why go on at all? Morning comes, but you don’t care. A voice in your head says it is time to get out of bed, but you have no desire to do so. You may not even have a reason. Life feels pointless. To get out of bed may as well be climbing a mountain. You feel heavy, and being upright takes something from you that you just don’t have to give.”

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler, On Grief and Grieving, p. 53

验收Acceptance

“接受常常与‘一切都好’或‘对所发生的一切感到满意’的概念相混淆。事实并非如此。我们永远不会喜欢这个现实,也不会让它变得更好,但最终我们会接受它。我们学会了与之共存,我们必须学会生活的新秩序,这也是我们最终的治愈和适应所指向的方向,尽管事实上治愈看起来和感觉起来都像是一种无法达到的状态。 治愈看起来像是回忆、追思和重构。 我们可能不再对上帝感到愤怒; 我们可能会意识到我们之所以会失去的常识性原因,即使我们从未真正理解。但我们的旅程还在继续。 现在还不是我们死亡的时候,事实上,正是我们痊愈的时候。”

伊丽莎白·库伯勒-罗斯和大卫·凯斯勒,《悲伤与悲伤》,第59-60页

“Acceptance is often confused with the notion of being all right or okay with what has happened. This is not the case. … We will never like this reality or make it okay, but eventually we accept it. We learn to live with it. It is the new norm with which we must learn to live. This is where our final healing and adjustment can take a firm hold, despite the fact that healing often looks and feels like an unattainable state. Healing looks like remembering, recollecting, and reorganizing. We may cease to be angry with God; we may become aware of the commonsense reasons for our loss, even if we never actually understand the reasons. … But our journey still continues. It is not yet time for us to die; in fact, it is time for us to heal.”

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kassler, On Grief and Grieving, p. 59–60